By

Dr R P Snaith

Psychiatrist and Chairman of Committee for Progressive Care and Rehabilitation

A knowledge of history is no mere diversion; without it, those fertile avenues of thought which have so often led to innovation and advance must be explored again, and without it the lesson of many a disastrous mistake which should have been learnt will be suffered once more.

The history of man’s attempts to understand and care for the mentally ill is a long one; disorder and disease of mind is not a new phenomena, a tragic by-product of industrialised society; the illnesses we now recognise and name have occurred in all societies both modern and ancient, rural and urban, sophisticated and primitive. In former times people usually assigned these disorders to malign influences or possession by devils. Ignorance of the nature of mental illness led to superstitious horror frequently accompanied by barbarous cruelty.

There were periods in history when more enlightened attitudes prevailed; the Greek physician, Hippocrates, who taught some 400 years before Christ, recognised mental disorder as sickness worthy of medical attention but such episodes were unfortunately brief and relapse into incomprehension followed. Even in our own age it is still considered by some that to suffer from mental illness is a shameful matter as if the sufferer were in some way responsible for his disorder.

The history of the great asylums is but one chapter in this story but it is certainly the most profitable one to study for it recounts the story of progress from universal ignorance to the present happier age of some understanding and of more effective treatment of mental disorder.

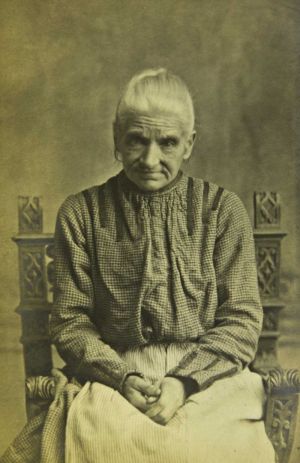

The word asylum means a place of refuge. The so called lunatic asylums were instituted to provide care for those who, by reason of disorder of mind could not cope with conditions in the community and could not afford to pay for private care. In their early days the patients were therefore largely drawn from the despised pauper class. The early nineteenth century overshadowed by the grim conditions of the Industrial Revolution was an age in which the welfare of the individual was a low priority of society; the pauper was treated little better than the criminal, and to suffer the double misfortune of being both financially destitute and mentally disordered placed the individual beyond the pale of civilization. It is therefore with some amazement that we read of the humane concern of those who planned, built and worked at the West Yorkshire Asylum. We read in the history that one of the first endeavours of the directors and administrators was to reduce the cost of maintenance of the individual in the asylum to a level comparable to that of the workhouse . To call this effort humane concern may at first sound paradoxical, but it was directly inspired by the realization that if the treatment was to have any chance of success, then the patients must be admitted at an early stage of their illness; so long as costs to the community of asylum care were high, the Poor Law Guardians would prefer to delay admission for as long as possible.

It is a somewhat ironical comment on these early endeavours, that in their success lay the seeds of future difficulties; for once the cost of maintenance was lowered the problems of overcrowding began. In Wakefield as throughout the country, requests for admission soon outstripped available space. More accommodation was tacked on to the original building in piecemeal fashion but even so, space was short. Added to this material discomfort arose what today would be called a ‘low staff-patient ratio’. The tendency to herding and regimentation began and the asylums lost much of their early high ideal of individual concern and care. The low point of what has been called the process of institutionalization was reached in the early decades of the present century. Then the long slow upward climb toward improved conditions began.

Throughout the country the word asylum ceased to be used and the institutions were renamed mental hospitals. As effective methods of treatment became available the quality of medical nursing staff improved, but for a further long period the mental hospitals continued to be the Cinderella of the nations medical services.

The hospitals benefited by their inclusion in a comprehensive National Health Service after 1948. Further enlightened legislation culminating in the Mental Health Act of 1959 has led to the present situation where the great majority of patients requiring treatment in a mental hospital are admitted without any legal restraints but as voluntary patients, free if they wish to discharge themselves as at other types of hospitals.

With the passing of the fear of loss of liberty, people began to accept the need for treatment early in the course of their illness, thus sparing themselves and their families, untold suffering. Everywhere, locks and bars were removed from the doors of wards and the gates and railings surrounding the hospitals came down. Relapse following initial recovery from a mental illness is still not uncommon, and for a while in the 1950s the familiar jibe went that the mental hospitals had replaced their closed doors with revolving doors. However, further improvements in treatment, and the establishment of greater numbers of outpatient clinics with more adequate after care facilities, has led to a great reduction in the number of relapses. The same provisions have enabled a large proportion of the mentally ill to receive treatment as out-patients and in their own homes without the need for admission to hospital.

It is true to say that today the conditions in mental hospitals can be favourably compared with those in general hospitals. The present situation will not however rest in a static for. Medical research continues to advance and treatments become ever more effective whilst nurses, doctors, psychologists and social workers acquire even greater skill in understanding and treating their patients.

For an understanding of the treatment of mental illness today, it is necessary to know something of it’s history. Shortly after the French Revolution a physician called Phillippe Pinel unchained the lunatics at the Bicetre Hospital in Paris. This celebrated event became symbolic of an awakening to a more humane approach to the mentally ill. Great reformers in Britain included William Tuke, a Quaker tea merchant who founded the York retreat, a hospital in which kindness and tolerance was to set the tone for future care of the psychiatric patient and provide an administrative model for the mental hospitals which were to be constructed after it. John Conolly effectively abolished all forms of mechanical restraint at the Middlesex asylum in Hanwell in 1839. The directors of the hospital at Wakefield were among the first to pioneer effective work therapy for their patients; this was mainly farm work and before long the farm was an integral feature of most mental hospitals in Britain.

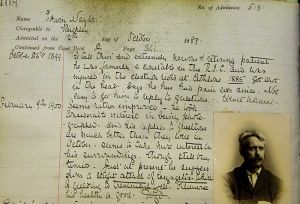

Yet there was still no real knowledge of the nature of mental illness, and the list of supposed causes from the history now provokes amusement

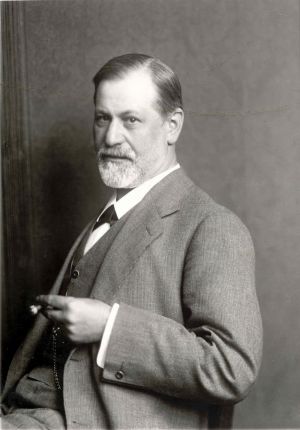

Sigmund Freud practised psychiatry in Vienna at the end of the last and the beginning of the present century. As a result of his immense energy and prolific writing, people realized that mental illness was a subject as worthy of medical study as the disease of the body. He evolved a method of treatment he called psychoanalysis by which he claimed that the origin of psychiatric disorder could be traced back to experiences occurring in the early years of life. The method of treatment was prolonged and could not be adapted to the vast numbers of people suffering from those severe disorders called psychosis in mental hospitals; moreover, many psychiatrists now believe Freud’s theories to be erroneous; but he has an unshakable place in history for he encouraged doctors to try to help their patients by listening to what they had to say. From psychoanalysis many methods of treatment based on verbal communication between doctor and patient have developed, all grouped under the general term psychotherapy. The search for more effective techniques of psychotherapy still continues.

Although frequently effective in the treatment of neuroses, that is the milder forms of psychiatric illness in which the patient’s contact with reality is not grossly disturbed, it is now generally accepted that forms of psychotherapy are of no more than marginal benefit for those suffering from the severer illnesses called psychoses who constituted the majority of those in the mental hospitals. Fortunately, however, major advances have been made in the treatment of these disorders also.

The psychoses have been divided into two broad groups: those in which there is a demonstrable disease of the brain, and those in which it is now believed there is a brain disorder the nature of which has not yet been completely elucidated. The first group are named organic psychoses and the second the ‘functional’ psychoses.

One of the forms of organic psychosis which was a major cause of admission to mental hospitals until a few decades ago, was the destruction of brain tissue by syphilis; at the end of the last century it accounted for a third of all admissions to mental hospital. Today techniques of diagnosis, effective treatment and prevention through public health and educational measures, has led to this disorder being a great rarity in psychiatric hospitals. However, other forms of organic psychosis are still common, and they are the various forms of advanced dementia occurring in the elderly; as yet there are no effective treatments for these disorders, but the mental hospitals play their part in providing nursing care when families can no longer manage their sick member.

Of the functional psychoses, two major types are recognised: manic depressive psychosis and schizophrenia. In the first, manic depressive psychosis, there occurs severe attacks of disorder dominated by depression or overactivity with intervening periods of normality. In the 1920s it was discovered that patients suffering from these attacks were rapidly restored to health if artificial convulsions resembling epileptic fits were induced. At first, such treatment was rather alarming and would probably have soon lapsed if it had not been so effective. It’s value however led to the search for safe methods of its administration and improved techniques of anaesthesia so that the patient experienced nothing more frightening than a short sleep. The method now used is called electro-convulsive or ECT, and is so safe and easy to administer that many patients receive the treatment as out patients.

The other major type of functional psychosis called schizophrenia was a severer disorder altogether, for the patient did not return to normal mental functioning between attacks, and for many sufferers the illness meant prolonged care or even a life-time in a mental hospital. This is not so today for in the 1950s pharmacologists and psychiatrists working together discovered a drug which was effective in controlling the disease and restoring the person to normality if it was given early in the course of the illness. This drug is called Chlorpromazine and belongs to a group of chemicals known as phenothiazines. Progressive research and refinements of the drug treatments have been so successful, that it is now rarely necessary for a patient developing schizophrenia to spend more than a month or two in hospital and very frequently recovery is complete so long as the drug treatment is continued. This control of one of the most distressing afflictions of mankind surely ranks as one of the greatest triumphs of medical science this century.

The drugs however, were not so effective in helping those who had already reached an advanced stage of the disorder and who had already been in hospital for many years. For many of these patients who developed schizophrenia before the advent of modern treatment, continued hospital care is still necessary. Some of them have in fact recovered to a large extent but owing to the duration of their stay in hospital thay have lost contact with their families and have come to regard the hospital as their home; owing to the vast improvements in hospital organization and facilities, many are quite content to stay in hospital. Some hospitals have engaged on policies of discharging previously long stay patients before adequate provision has been made for them in the community. This has led to a pathetic increase in the number of homeless people drifting from one poor type of accommodation to another; It has not been the policy atStanleyRoydHospital.

It should not be thought that those patients remaining in hospitals for years are either neglected or forgotten. Indeed they are the very centre of attention for the progressive care and rehabilitation teams composed of all members of the hospital staff, nurses, doctors, administrators, occupational therapists, social workers and psychologist. As a result of the efforts of theses teams in the mental hospitals patients are helped to achieve a higher standard of life, redeveloping social and occupational skills which they had long forgotten. They now find satisfaction in work in small hospital based workshops where they are paid to do realistic work contracted out from local industries: they enjoy social evenings, shopping days in the town, day trips in the summer and even annual summer holidays. The one time strict seclusion of the sexes has been overcome and men and women engage in more normal social life and contact together.

All content copyright protected.