Written For ‘Contact’ High Royds Staff Magazine, October 1971

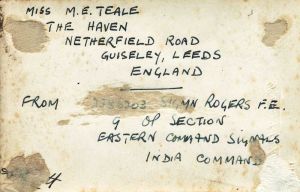

Fred, Eric Rogers gives us a wonderful insight into hospital life from the 1920’s.

Those were the Days!!! By FE Rogers.

Having decided to relinquish my post as doyen of the clerical corps at High Royds Hospital and to abdicate my position as oldest inhabitant ( by virtue of service, not age) it is inevitable that I should recall what the hospital ( then the West Riding Asylum) was like almost half a century ago when with some trepidation I walked up the front drive for my interview. Employment for school leavers was almost unobtainable and I counted myself lucky to be the one selected from 46 applicants, all of whom had school certificates and many, the Northern Universities’ Matriculation Certificate.

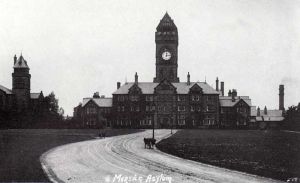

There were no trees then on Thorpe Lane, so that the asylum buildings were most impressive when viewed from White Cross, albeit the main tower with it’s tiled belfry atop looked like a grey old man wearing a red dunce’s cap. The belfry housed a single bell which marked the hours day and night. I later knew a patient who was firmly convinced that every time the bell tolled, an inmate was hanged at the Pumping Station. He would doff his cap, cross himself and mutter “Another one gone, poor soul!”

I reached the front door and rang the day bell, whereupon an impressive figure wearing a frock coat, with a cravat and an enormous tiepin, opened the door, bowed from the waist and enquired “What is your business, sir, please?”. This was the standard form of address for every visitor, whatever his status. This individual, the Hall Porter, was on duty from 5.30 am to 10.30 pm with one sliding day off per week. These hours entailed his sleeping on the job; his twin rooms, office and bedroom, are still there on the “Centre”.

I was interviewed for this very minor post of office boy ( which included fire-lighting, floor sweeping and brasses cleaning, all for ten shillings a week) by no less personages than the Chairman of the Visiting Committee, ( a Leeds Alderman), the Architect to the Asylums Board, the Medical Superintendent, and the Clerk of Works. Throughout the interview, I was distracted by the Alderman’s enormously bulbous and scarlet nose. Some years later a portrait of this gentleman hung ceremoniously in the Committee Room, but for this purpose his proboscis had been suitably “touched up” so that if he appeared, if not handsome, at least almost normal.

On the morning I began work there was deep snow and I found the Timekeeper and his wife searching for a lost key. As this was never found and the person responsible would not own up, the Medical Superintendent ruled that, as a punishment, the staff from Guiseley would no longer use the gate in question ( then at the east end of the General Stores). Consequently all staff from that direction had to come in by the Laundry Drive until in the summer, it was found that they were taking a short cut across the cricket field and ruining the turf of the square, so permission to use the underpass ( now governed by traffic lights) was restored.

At the entrance to each drive stood a massive wrought iron carriage gate and a handgate hung on stone pillars. The carriage gates were locked from dusk to dawn and anyone requiring admittance had to pull the big pendant handle which rang a bell in the lodge. Very few vehicles used the drives as most goods were delivered in bulk via the private railway siding. Only the occasional two-horse railway dray or the horse drawn ambulances from Leeds and Bradford were to be seen, except on visiting afternoons, Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays or Committee Day once a month, when Waite’s Livery Stables ran a shuttle service of cabs from Guiseley Station.

Only two motor vehicles were in evidence; the Works Department Ford Ton Lorry and Medical Superintendent’s Armstrong- Siddeley. Petrol for these was obtained in two-gallon cans from Guiseley and stored (separately) in the Oil Store. The drives were poorly lit by gas lamps – the lamp lighter with his long stick igniting them at dusk and returning to extinguish them at10.30p.m.

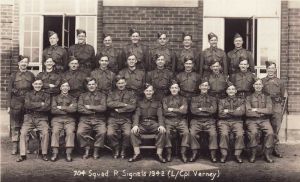

Staff worked long hours and suffered many restrictions. The newest members had to live in for an indefinite period, sleeping either on the wards ( at least one on each ward in case of fire) or in the three residence, one of which (no3) was the married quarters. The period of living in varied according to the recruitment position; one could still be living in after three years, or be lucky enough to be “out” in six months. Living in staff were required to be in their quarters by 10.30 pm unless in possession of a late pass, when they would have to report at the only door open, on the Laundry Drive, at the end of the “female” corridor. Nevertheless there seemed to be no dearth of candidates for the posts of Attendants and Nurses(sic) although qualifications asked for had no relevance to nursing but were, for example, football or cricket skills, singing, acting or the playing of an instrument. This was because the duties were more custodial than remedial and the skills were required for the entertainment of staff and patients in a somewhat isolated environment by way of the excellent orchestra, stage players, games teams and choir. The male staff were largely recruited locally and many lived in the houses at Menston then known as “The Barracks”, which had been privately erected by an enterprising builder for this purpose when the Asylum was opened. Many of the female staff were “foreigners”, largely Irish, and locally their reputations were, rightly or wrongly, suspect. The stretch of road between White Cross and Hare and Hounds then bare of buildings except for the lodge houses, was their place of promenade, particularly on Sunday evenings and was known as “The Bunny Run”. Many a local mother exhorted her teenage son to “Keep away from them ‘Sylum Totties” (short for “Hottentots”)

But if the life of the staff was hard, that of the patients was even more spartan. The system of certification meant that usually admission was delayed until all hope of improvement was gone; accordingly to enter the Asylum was in effect a life sentence of incarceration. The wards were dark, being painted in bottle green or chocolate brown, with bare wooden floors or at best, dark brown linoleum. The furniture was heavy and designed to resist damage rather than to provide comfort; there were no curtains, only blinds for privacy. A few pictures, poor reproductions of famous paintings, were on the walls. True, every ward had it’s caged canary, whose singing was supposed to brighten the lives of the inmates, but no doubt many drew comparisons between their own state and that of the imprisoned bird. Every ward, too had it’s piano, and the male wards their billiard tables but there was as yet, of course, no radio, cinema and nor for a long time, television. At night the wards were even more dismal, having very sparse incandescent gas lighting. Some of the sanitary spurs even had no hot water for washing.

Meals were taken in the large dining halls, except for the sick wards and Sunday services never had less than 600 attending (even though like the Army Church Parades it was a matter of compulsion rather than inclination). Smoking was completely forbidden to staff on duty, on pain of instant dismissal, and only permitted to male patients in dayrooms and corridors. Women did not smoke at all unless they were “fast”.

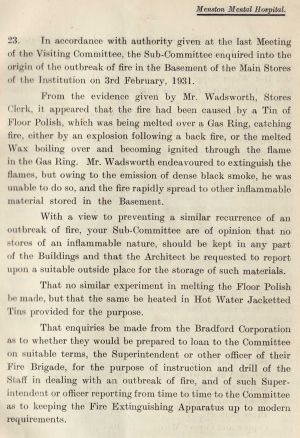

Safety consciousness was at a premium – staff went their rounds at frequent intervals during the night, pegging- in at every dayroom and dormitory so that their presences were recorded on a time clock in the Medical Superintendent’s office, the record being closely scrutinised each morning. Open fires were protected by padlocked guards, patients were not in any circumstances allowed to have matches; w.c. pulls were enclosed as a precaution against hanging; even the gas brackets on staircases were so designed that they collapsed if anything was hung upon them. Fires seemed much less frequent than today – perhaps this was because the minor outbreaks were not reported, and one only knew of a fire if it got out of hand.

The “Centre” was a Holy of Holies. Only those with bona fide business were allowed to set foot in it. Even so, unless you wore rubber soled shoes, you would find that the door of the Medical Superintendent’s Office would open, and “The DOCTOR” himself would glare at you over his glasses, not saying a word. But one felt about six inches high, yet at the same time prominent and vulnerable.

The lawns and shrubberies were immaculate – innumerable patients were dragooned into this work and into farming as a sort of primitive occupational therapy. The lawns in particular were as sacrosanct as an army parade ground. Once I began to walk across the lawn that then filled the middle of the works department yard, but was ordered back and make to walk round. Another beautiful lawn, flanked by a row of magnificent sycamores, occupied the position where the General Stores Oil Store now stands. At one time a path developed diagonally across it and the Medical Superintendent determined to catch the person responsible, lay in wait in the General Stores Office, declaring that the first person to cross that lawn would “go down the drive”. Unfortunately that person turned out to be his own wife. History does not record what punishment he meted out to her.

Such were the “good old days”. Or were they….?